A whitetail rises from its bed in the spring woods. Hunters now know how many doe licenses are available for chasing such deer this fall.

Bob Frye/Everybody Adventures

The Pennsylvania Game Commission wants to maintain the deer herd at existing levels in most, if not all, of the state.

The continued presence of chronic wasting disease is one reason why.

Pennsylvania Game Commissioners allocated doe licenses at their recent board meeting. They largely followed the recommendations of their deer biologists, with only a few, mostly small, changes made to what was proposed.

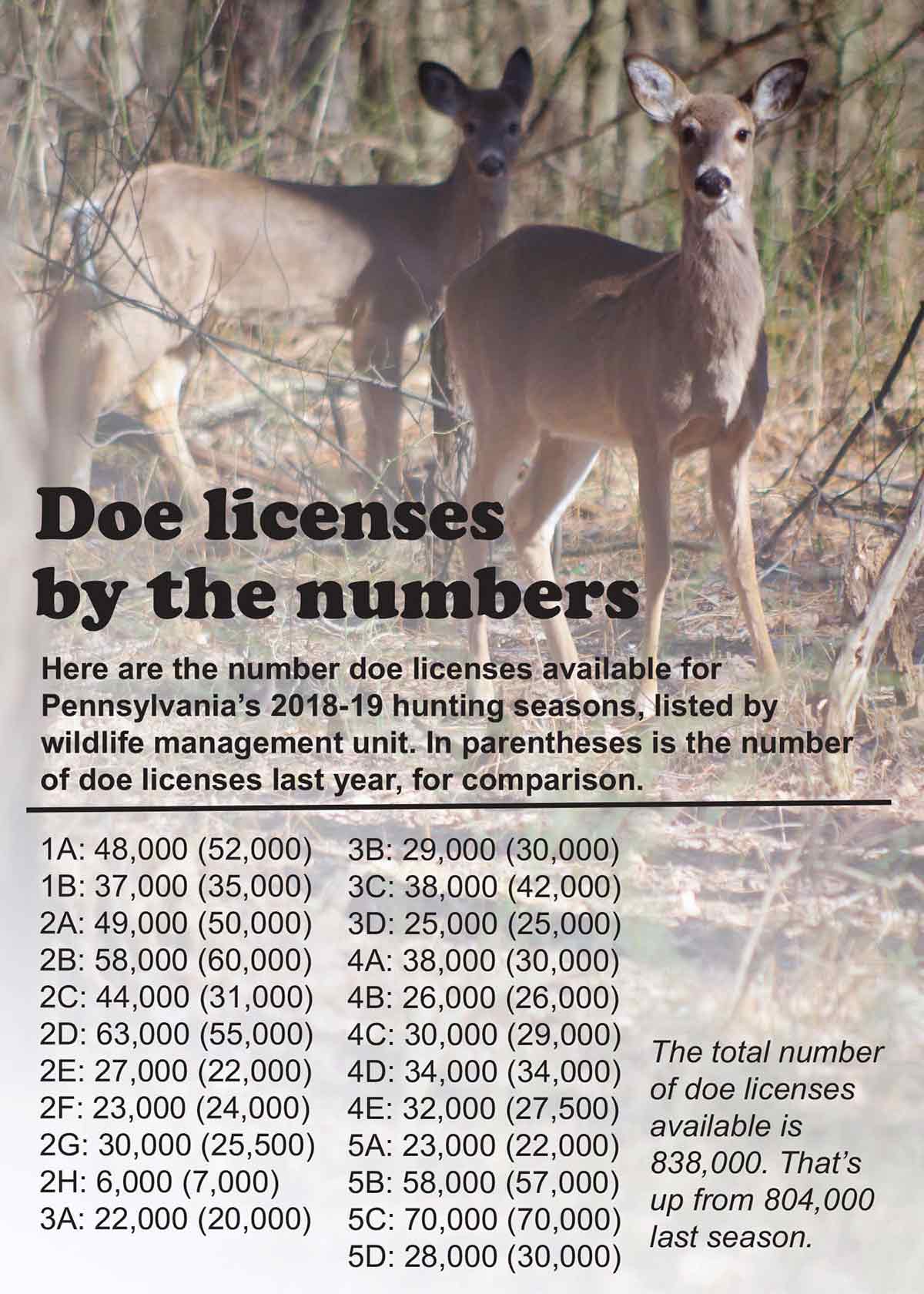

In four of 23 wildlife management units — 2C, 3A, 4C and 4E — the deer herd increased in recent years. The commission doesn’t want to reduce those populations, but it does want to prevent them from getting any larger.

So to keep things “stable,” the number of doe licenses available in each for 2018-19 is up over last season. The biggest jump is in 2C, where the doe allocation went from 31,000 a year ago to 44,000 this fall.

The goal is to maintain stable deer population in 16 other units. That means more doe licenses in some, fewer in others, the same in a couple.

In three units – 2D, 2E and 2G – the goal is to reduce the herd. All have more doe licenses this year than last, although in the case of 2G, commissioners upped it only from 25,500 to 30,000, rather than the 39,000 biologists proposed.

None of that is markedly different from past years. Allocations routinely go up or down, depending on deer and forest health and acceptable levels of deer-human conflict.

What’s different this time around is how much disease is also playing a role.

Chris Rosenberry, head of the commission’s deer and elk section, pointed out that chronic wasting disease continues to spread across the state. The number of sick deer continues to grow, as does the geographic area where the disease is present.

“And that has influenced our recommendations in a number of units,” he said.

Specifically, that’s the case in four.

Units 2C and 4A are showing the kinds of forest regeneration that might otherwise allow for their deer herds to grow. But both also lie, at least in part, within disease management area 2. It’s the hottest of hot spots for wasting disease in the state.

That trumps any other positives going on there and necessitates maintaining their deer herds where they are, he noted.

Units 2D and 2E, meanwhile, have healthy deer populations. Hunters kill more bucks per area there than anywhere else in the state.

The concern is that if wasting disease gets into those populations, the size of the deer herd might allow it to spread quickly, Rosenberry said. No one wants that, so the goal is to reduce the herds.

Disease management area 2 shows why.

Less than 3 percent of the deer tested there – killed by hunters, collected dead along roads or otherwise killed – are positive for wasting disease, Rosenberry said.

Still, that is growing each year. That’s concerning for two reasons.

The first involves hunters.

West Virginia and Wisconsin saw similarly low disease rates in the first few years of their outbreaks, Rosenberry said. But things changed quickly.

In some areas of Wisconsin, for example, 25 percent of deer have the disease.

“According to preliminary results from our most recent deer hunter survey here in Pennsylvania, if CWD infections reach the level observed in West Virginia and Wisconsin, about a third of our Pennsylvania deer hunters say their interest in deer hunting will decline,” Rosenberry said.

That would hamstring the commission, as hunters are its chief tool for managing whitetails.

“So obviously this is a significant concern for the future of deer and CWD management efforts,” Rosenberry added

The second involves deer.

Rosenberry said recent research done in Wyoming suggests that deer infected with wasting disease survive at only about half the rate as healthy deer.

A deer population with no wasting disease can be managed to stay the same size over 25 years, he said, so long as the commission knows things like harvest rates. If wasting disease is present in even 3 percent of those animals, though, and those animals survive only half as long as their healthy counterparts, things change.

“Over a 25-year period, that deer population potentially declines by about a third,” Rosenberry said.

The disease is hard to detect and harder to control, he said. It’s hard to predict where it might go, too.

“So we’re never going to have that black and white moment,” said commission president Tim Layton of Somerset County.

“I don’t think so,” Rosenberry replied.

In the meantime, all the commission can do is work with the knowledge it has to do the best it can to manage it for now, he added.

“Our antlerless deer license recommendations are one part of our attempt to do more to address the threat of CWD to deer and deer hunting in Pennsylvania,” Rosenberry said.

Bob Frye/Everybody Adventures