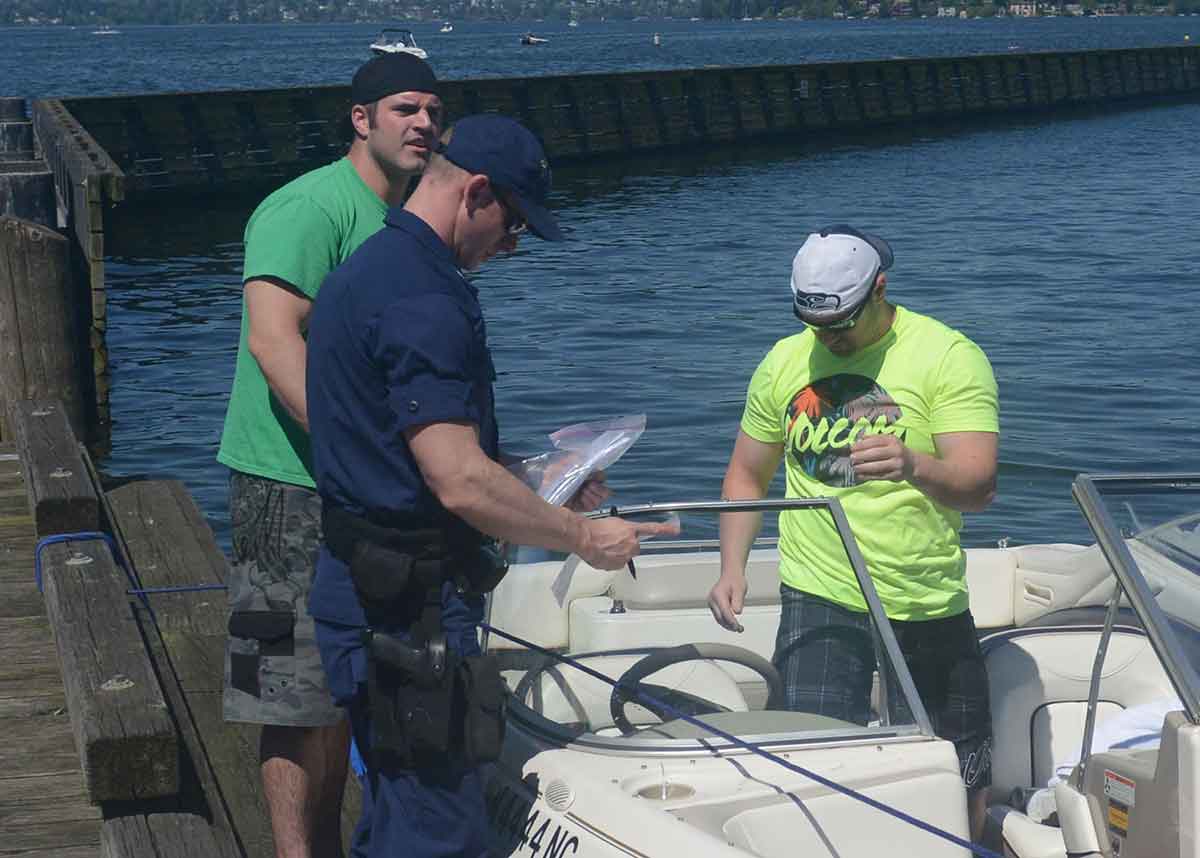

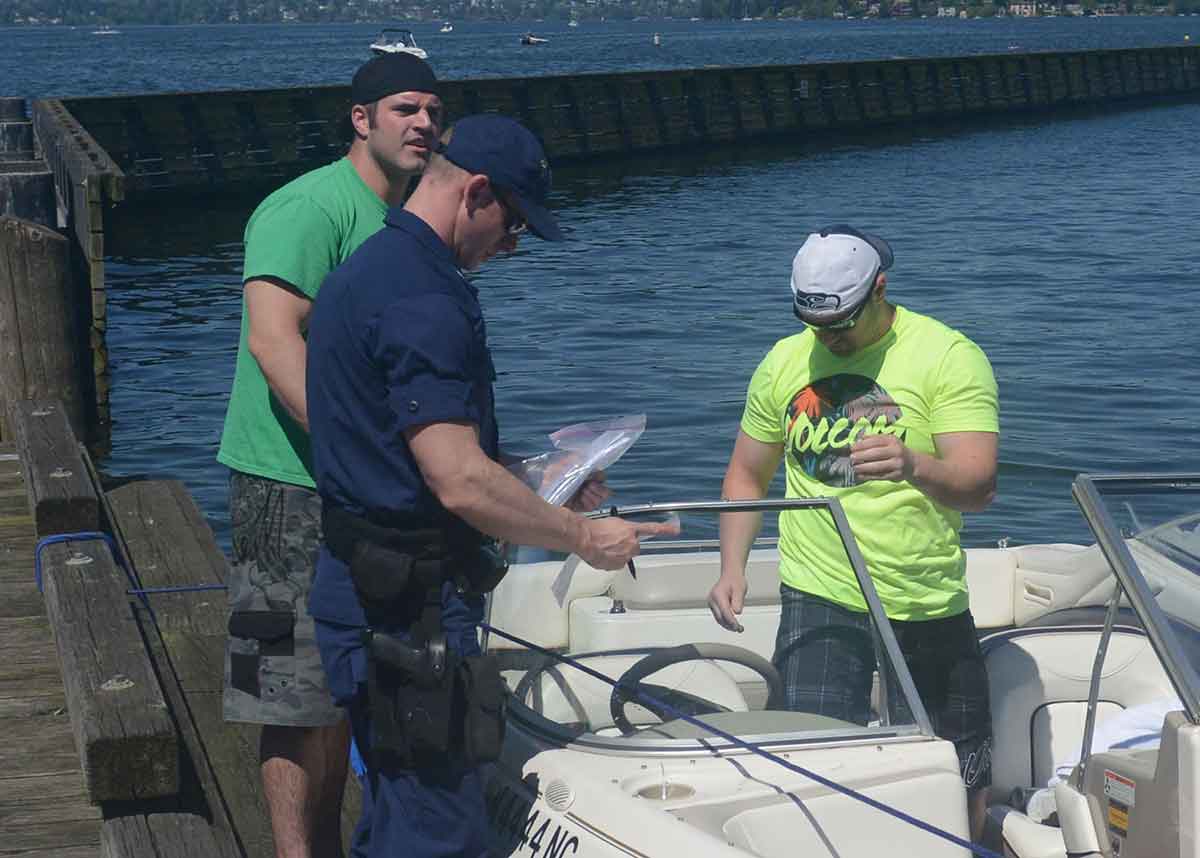

Law enforcement officials across the country are using new tools to test boaters for excessive alcohol use.

Photo: WikiCommons

It’s a new way to fight an age-old problem.

Sometimes, people drink alcohol when out boating. And, as a result, some of them die.

But there are new tools out there for detecting who’s had too much.

The U.S. Coast Guard recently released its 2018 Recreational Boating Statistics report. It looks at boating accidents nationwide, their causes, impacts and costs.

The news was largely good.

The report noted that, in 2018, there were 4,145 reportable boating accidents across America. They resulted in 633 deaths, 2,511 injuries and roughly $46 million in property damage.

Those numbers, while still large, are down compared to 2017.

Specifically, accidents were down 3.4 percent, deaths 3.8 percent and injuries 4.5 percent.

But booze and boating continue to be a bad combination.

It’s simple inattention that causes most accidents. “Operator inattention,” the Coast Guard said, caused 654 accidents and 437 injuries. But that led to just 50 deaths.

Likewise, the similar “improper lookout” caused 440 accidents and 316 injuries. That led to 27 deaths.

By comparison, alcohol use led to just 254 accidents and 204 injuries. But it caused 101 deaths. That’s 19 percent of the total.

No other single factor played a role in so many fatalities.

“It is heartbreaking to realize that more than 100 people could still be alive today had alcohol use been curbed,” said Capt. Scott Johnson, chief of the Office of Auxiliary and Boating Safety at Coast Guard Headquarters.

Law enforcement agencies have made a point of trying to stop people from drinking too much and boating in recent years. Operation Dry Water is the name given to a nationwide effort to educate the public about the dangers of drinking and boating.

In the not-too-distant past, though, officers faced a problem.

They relied on a standardized, on-shore battery of tests to detect boating under the influence cases, said Corey Britcher, chief of the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission’s law enforcement bureau. That included things like having people stand on one leg or make a walking turn.

Since three to four years ago, however, officers also use an on-the-water, seated battery of tests that were studied and vetted by the Coast Guard, Boating Law Administrators and university researchers. They include things like touching a nose with a finger, counting movement of hands and more.

“They’re all distracted attention tests that, if you ‘re not at 0.08 or above, you should be able to listen to the instructions and do those tasks,” Britcher said.

Officers have to be certified in doing on-shore testing before they can get certified in those on-boat tests, he said. But commission officers are.

A lot of other police – from municipal officers to state troopers – are starting to make use of the tests, too, though, Britcher said. Many sign up for commission training classeswhen offered.

The reason is those tests allow them to test accident victims, handicapped drivers and others who can’t tand or walk, he noted. Some troopers, he said, have even begun carrying folding camp chairs to use with just such people, he added.

No one has challenged the validity of the tests in Pennsylvania court, Britcher said. But he said they would withstand any scrutiny.

“There’s a lot of rigor that goes into it. They are sophisticated tasks that have been vetted,” agreed commission executive director Tim Schaeffer.

Eliminating excessive alcohol use alone won’t save everyone on the water. There are other problems, too.

Johnson pointed to life jackets – and the fact people don’t always wear them – as another issue.

Last year, as is usually the case, drowning accounted for three out of every four deaths. And, as is typical, most of those who drowned – 84 percent — did not have a life jacket on.

Boating education – or the lack of it – was again a major player in boating accidents. Three of every four boating deaths occurred on boats where the operator had no formal training.

“Only 18 percent of deaths occurred on vessels where the operator had received a nationally approved boating safety education certificate,” the Coast Guard report reads.

Open motorboats – at 50 percent of cases – were involved in the most fatal accidents. A total of 311 people died in accidents involving them.

Kayaks were next at 13.5 percent, followed by canoes at 7. Together, they were involved with 128 deaths.

Collisions with other boats (at 1,028) were the most common type of accident, and led to the most injuries (661).

Falls overboard accounted for the most deaths, however. A total of 159 people died in 274 falls overboard, meaning more than one of every two people who went over the side never came back.

As for when accidents and deaths occur, they’re not necessarily related as closely as some might think.

Accidents peak in summer, as would be expected. July was the worst month for accidents in 2018. There were 1,016 then, followed by June with 687 and August with 651.

They produced the most deaths, too, thanks to that sheer volume. There were 102 fatalities in June, 100 in August and 88 in July.

But, according to the report, people who go into the water in courtesy of a boating accident are far more likely to die at other times. January, April, November, October and December are when most people die.

MORE FROM EVERYBODY ADVENTURES

See also: Cold water boating fun, but safety paramount

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.