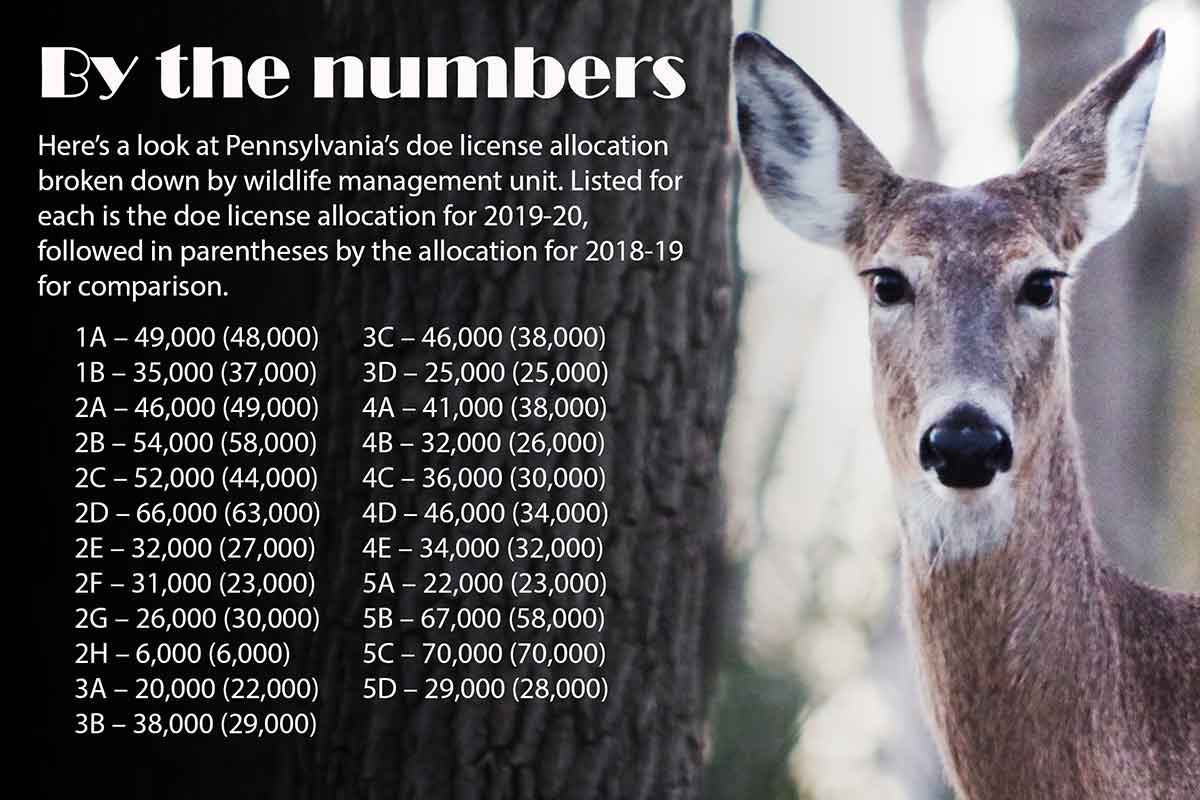

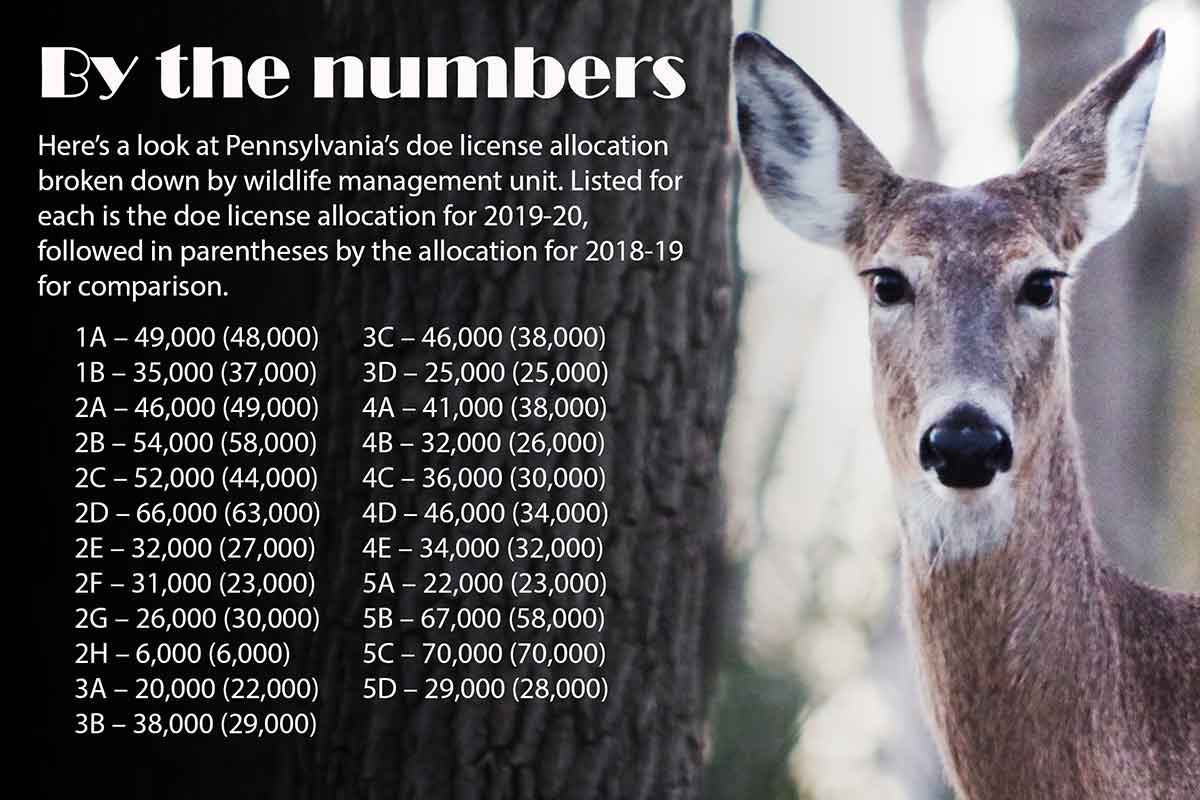

There will be more antlerless licenses available in some places but not others in Pennsylvania this fall and winter.

Bob Frye/Everybody Adventures

Don’t get too comfortable.

Yes, it’s true that, statewide, there will be more antlerless deer licenses available in Pennsylvania this fall than last. Pennsylvania Game Commissioners allocated 903,000 doe tags for the 2019-20 hunting seasons. That’s up 65,000 from 2018-19’s 838,000.

But the increase is not spread evenly across the state.

In fact, six of the state’s 23 wildlife management units – roughly a quarter — will offer fewer doe tags this year than last. In three more, this year’s allocation is identical to last years.

So in those places, hunters there will need to be as diligent as ever in getting their applications in on time, lest they risk not getting a tag.

As for the other units, 14 are offering more doe tags this year than last. In nine the increase might be termed significant, meaning an additional 5,000 tags or more. One is offering 12,000 more – an increase of roughly 33 percent.

There are largely two reasons for all that: forests and disease.

Chris Rosenberry, head of the commission’s deer and elk section, said deer populations are increasing in three of the state’s 23 wildlife management units: 2F in the northwest, 4C in the southcentral and 5B in the southeast. They are stable in the other 20.

In four of the latter, though, deer impacts on forest health are “high.” In short, those forests are not adequately regenerating, in part because of hungry deer browsing heavily on new growth.

Those four – units 3B, 3C, 3D and 4E — are all located in the northeast region.

That’s not to say their deer populations are exceedingly large necessarily, said commission president Tim Layton of Somerset County. But when forests are struggling to grow, he said, even a relatively low number of deer pose problems.

“It’s that the forest is struggling to come back and any amount of deer, really, is not good for that area,” Layton said.

Deer are not the only thing impacting forest health in those units, Rosenberry said. But, he added, they are the only thing the commission can control.

So he recommended increasing the doe license allocation in each. Commissioners agreed in three cases.

The exception was unit 3D. It had 25,000 doe tags last year. Rosenberry wanted 37,000 this year.

But commissioner Stanley Knick of Luzerne County said he hears complaints from hunters there about too few deer already. So he suggested replicating last year’s allocation of 25,000. The board went along with that.

Rosenberry also suggested bumping up the number of doe tags – again, considerably in cases – in six wildlife management units where the commission has found chronic wasting disease, or CWD, in free ranging deer. They are 2C, 2D, 2E, 4A, 4B and 4D.

That’s an attempt to curb the disease’s spread, he explained.

“Based on our experience in Pennsylvania, CWD continues to increase at current deer population levels. Thus, our recommendation for lower deer levels,” Rosenberry said.

One commissioner, though, wondered if the allocation increases are enough.

Statistics show it takes issuing four to five doe licenses to get one deer actually killed. So, for example, going from 44,000 doe tags in unit 2C last year to 52,000 this year might mean an additional 2,000 deer killed over nearly 3,000 square miles.

Commissioner Jim Daley of Butler County wondered if that’s enough.

“If we are really serious about CWD, why such small increases? That’s not going to do much for us,” he said.

Rosenberry said controlling the disease is a long-term effort. Add the bump in doe tags this year to the fairly large increases last year over 2017-18 and the commission is indeed “ramping up” efforts to lower deer numbers, he said.

Beyond that, he encouraged hunters to use deer management assistance program permits – good for antlerless deer on specific properties – to lower deer numbers where disease rates are highest.

Daley had another question.

The commission’s formula for determining whether to raise, lower or maintain deer numbers in a particular unit examines forest health. That’s fine, he said, as trees are a crop.

But it doesn’t seem to similarly take agriculture into account, he said. And he thinks it should.

“I still believe somehow we need to get a measure of agricultural impacts into these numbers. We don’t have it,” Daley said. “We just clearly don’t have it.”

That’s hard to calculate, Rosenberry said. There is no quantifiable data set for agricultural health like with forests.

Rather, what one farmer deems acceptable deer damage another doesn’t.

“Really that comes down to a human tolerance level,” Rosenberry said.

And the commission tries to account for that, he said.

The commission looks at three things in making deer management decisions. Forest health and deer health are two. “Deer-human conflicts” – everything from deer-vehicle collisions to homeowner complaints to agriculture — is the third, Rosenberry said.

Daley, though, said the commission “ought to pay a little more attention” to the concerns of farmers and vegetable growers.

“They’re all suffering, sometimes considerably,” he said.

Want to see more? Check us out on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.